Marx, Kuznets and FIAT Currency

Angel Theory Part 3.3

The GDP Game (Audacious Economics)

The Theory of Every Business 2.0

A work in progress by Nick Ray Ball 16th January 2017

PRESENTING:

Chapter 3: Cube vs Pyramid and FIAT Currency

Along this journey we examine the differences between the US Federal Reserve and Pyramid/Ponzi Schemes in comparison with the Gold Standard Cubic financial gravity of the S-World Bond.

In 7,318 Words

Version 6.95-t-k2

Capital in the Twenty-First Century

Before we go to Tim Delmastro’s documentary ‘End of the Road: How Money Became Worthless’ and the FIAT currency, we will start this chapter with a whiz through economic history courtesy of Thomas Piketty’s ‘Capital in the 21st Century,’ in an attempt not to overly worry the reader, as many extreme economic predictions have been made in history, and none have come true.

Please note that the text in this font, that does not have a source is by Thomas Piketty staring with:

Malthus, Young, and the French Revolution

For Thomas Malthus, who in 1798 published his Essay on the Principle of Population, there could be no doubt: the primary threat was overpopulation. One particularly important influence was the travel diary published by Arthur Young, an English agronomist who travelled extensively in France from 1787–1788, on the eve of the French Revolution.

France at that time was by far the most populous country in Europe and therefore an ideal place to observe. The kingdom could already boast of a population of 20 million in 1700, compared to only 8 million for Great Britain (and 5 million for England alone). The French population increased steadily throughout the eighteenth century, and by 1780 was close to 30 million.

There is every reason to believe that this unprecedentedly rapid population growth contributed to a stagnation of agricultural wages and an increase in land rents in the decades prior to the explosion of 1789.

When Reverend Malthus published his famous Essay in 1798, he reached some radical conclusions, he was very afraid of the new political ideas emanating from France, and to reassure himself that there would be no comparable upheaval in Great Britain he argued that all welfare assistance to the poor must be halted at once and that reproduction by the poor should be severely scrutinized lest the world succumb to overpopulation leading to chaos and misery!

As we know, England did not stop welfare assistance or put in place any low population mechanisms. But France did revolt, and I dare say if they did not overpopulate, this would not have happened, and we would have a very different world today. It is of course worth mentioning that in 1979 China did introduce a one-child policy.

Huge disparities in per capita (all income / all population) income are created by overpopulation, and continue today, if we look at Southern Africa, Malawi, and the countries it borders.

| Country | Population | GDP | Per Capita |

| Malawi | 18.09 | 5.44 | $ 301 |

| Zimbabwe | 16.15 | 16.29 | $ 1,008 |

| Botswana | 2.25 | 15.27 | $ 6,788 |

| Mozambique | 28.8 | 11.01 | $ 382 |

| Zambia | 16.59 | 19.55 | $ 1,178 |

A quick look at the above and in terms of the average an individual earns, Botswana wins by a country mile 6 times greater than any rival, and the average Botswanan makes more than 20 times the average Malawian, and the obvious statistic in common is overpopulation.

Ricardo: The Principle of Scarcity

Most contemporary observers—and not only Malthus and Young—shared relatively dark or even apocalyptic views of the long-run evolution of the distribution of wealth and class structure of society. This was true in particular of David Ricardo and Karl Marx, who were surely the two most influential economists of the nineteenth century and who both believed that a small social group— landowners for Ricardo, industrial capitalists for Marx—would inevitably claim a steadily increasing share of output and income.

He was above all interested in the following logical paradox. Once both population and output begin to grow steadily, land tends to become increasingly scarce relative to other goods. The law of supply and demand then implies that the price of land will rise continuously, as will the rents paid to landlords. The landlords will therefore claim a growing share of national income, as the share available to the rest of the population decreases, thus upsetting the social equilibrium. For Ricardo, the only logically and politically acceptable answer was to impose a steadily increasing tax on land rents.

This sombre prediction proved wrong: land rents did remain high for an extended period, but in the end the value of farm land inexorably declined relative to other forms of wealth as the share of agriculture in national income decreased.

It would be a serious mistake to neglect the importance of the scarcity principle for understanding the global distribution of wealth in the twenty-first century. To convince oneself of this, it is enough to replace the price of farmland in Ricardo’s model by the price of urban real estate in major world capitals, or, alternatively, by the price of oil. In both cases, if the trend over the period 1970–2010 is extrapolated to the period 2010–2050 or 2010–2100, the result is economic, social, and political disequilibria of considerable magnitude.

Marx: The Principle of Infinite Accumulation

By the time Marx published the first volume of Capital in 1867, exactly one-half century after the publication of Ricardo’s Principles, economic and social realities had changed profoundly: the question was no longer whether farmers could feed a growing population or land prices would rise sky high but rather how to understand the dynamics of industrial capitalism, now in full blossom.

The most striking fact of the day was the misery of the industrial proletariat. Despite the growth of the economy, or perhaps in part because of it, and because, as well, of the vast rural exodus owing to both population growth and increasing agricultural productivity, workers crowded into urban slums. The working day was long, and wages were very low. A new urban misery emerged, more visible, more shocking, and in some respects even more extreme than the rural misery of the Old Regime. Germinal, Oliver Twist, and Les Misérables did not spring from the imaginations of their authors, any more than did laws limiting child labour in factories to children older than eight (in France in 1841) or ten in the mines (in Britain in 1842).

In fact, all the historical data at our disposal today indicate that it was not until the second half—or even the final third—of the nineteenth century that a significant rise in the purchasing power of wages occurred.

From the first to the sixth decade of the nineteenth century, workers’ wages stagnated at very low levels—close or even inferior to the levels of the eighteenth and previous centuries. This long phase of wage stagnation, which we observe in Britain as well as France, stands out all the more because economic growth was accelerating in this period.

In any case, capital prospered in the 1840s and industrial profits grew, while labour incomes stagnated. It was in this context that the first communist and socialist movements developed. The central argument was simple: What was the good of industrial development, what was the good of all the technological innovations, toil, and population movements if, after half a century of industrial growth, the condition of the masses was still just as miserable as before. People therefore wondered about its long-term evolution: what could one say about it?

This was the task Marx set himself. In 1848, on the eve of the “spring of nations” (that is, the revolutions that broke out across Europe that spring), he published The Communist Manifesto, a short, hard-hitting text whose first chapter began with the famous words:

“A spectre is haunting Europe—the spectre of communism.”

The text ended with the equally famous prediction of revolution: “The development of Modern Industry, therefore, cuts from under its feet the very foundation on which the bourgeoisie produces and appropriates products. What the bourgeoisie therefore produces, above all, are its own gravediggers. Its fall and the victory of the proletariat are equally inevitable.”

Over the next two decades, Marx laboured over the voluminous treatise that would justify this conclusion and propose the first scientific analysis of capitalism and its collapse. This work would remain unfinished: the first volume of Capital was published in 1867, but Marx died in 1883 without having completed the two subsequent volumes. His friend Engels published them posthumously after piecing together a text from the sometimes obscure fragments of manuscript Marx had left behind.

Like Ricardo, Marx based his work on an analysis of the internal logical contradictions of the capitalist system. He therefore sought to distinguish himself from both bourgeois economists (who saw the market as a self-regulated system, that is, a system capable of achieving equilibrium on its own without major deviations, in accordance with Adam Smith’s image of “the invisible hand” and Jean-Baptiste Say’s “law” that production creates its own demand), and utopian socialists and Proudhonians, who in Marx’s view were content to denounce the misery of the working class without proposing a truly scientific analysis of the economic processes responsible for it. In short, Marx took the Ricardian model of the price of capital and the principle of scarcity as the basis of a more thorough analysis of the dynamics of capitalism in a world where capital was primarily industrial (machinery, plants, etc.) rather than landed property, so that in principle there was no limit to the amount of capital that could be accumulated.

In fact, his principal conclusion was what one might call the “principle of infinite accumulation,” that is, the inexorable tendency for capital to accumulate and become concentrated in ever fewer hands, with no natural limit to the process.

This is the basis of Marx’s prediction of an apocalyptic end to capitalism: either the rate of return on capital would steadily diminish (thereby killing the engine of accumulation and leading to violent conflict among capitalists), or capital’s share of national income would increase indefinitely (which sooner or later would unite the workers in revolt). In either case, no stable socioeconomic or political equilibrium was possible.

Marx’s dark prophecy came no closer to being realized than Ricardo’s. In the last third of the nineteenth century, wages finally began to increase: the improvement in the purchasing power of workers spread everywhere, and this changed the situation radically, even if extreme inequalities persisted and in some respects continued to increase until World War I.

Comment from Nick Ray…

In studying and editing this section about the economists Thomas Malthus, David Ricardo, and famously Karl Marx, it seems that in each case their future predictions were based in their current circumstances. Thomas Malthus saw mass overpopulation lead France to revolution and wrote of the perils of overpopulation going forwards, which are now a significant worry going forwards but did not come to pass in the period he made his prediction.

David Ricardo wrote of the scarcity of land and it leading to a greater and greater income inequality, because that was what was happening at the time he wrote his prediction based on same, unaware that in 50 years’ time, the industrial revolution saw a lowering in the price of land.

And famously, Karl Marx wrote about what was happening in his time, and projected it forwards as his theory of infinite acumination, only to see inequality to decrease from 1870 to 1950 due to the World Wars, Revolutions, US Depression, and ripple effects of same.

In the case of Ricardo and Marx, both made future predictions on current circumstances and did not factor in yet unforeseen changes. They did not factor for Black Swan, ‘an unpredictable or unforeseen event,’ typically one with extreme consequences.

And they certainly did not set about creating a system like Angel Theory to replace the idea of predicting the future instead to making the future. And for more on this, see M-Systems 12. S-World UCS, 13. UCS Voyager, & 14 Angel Cities.

For now, and for this chapter, it is enough to know that historical economists’ prophesies of doom have not been born out, but that is not to say they are not useful tools, one still applies the logic, but considers the logic of only one of a few, or sometimes many sources.

Before we get to the principal of S-World Bonds becoming an insurance for a FIAT currency collapse, we must look at the work of Simon Kuznets.

From Marx to Kuznets, or Apocalypse to Fairy Tale

Turning from the nineteenth-century analyses of Ricardo and Marx to the twentieth-century analyses of Simon Kuznets, we might say that economists’ no doubt overly developed taste for apocalyptic predictions gave way to a similarly excessive fondness for fairy tales, or at any rate happy endings. According to Kuznets’s theory, income inequality would automatically decrease in advanced phases of capitalist development, regardless of economic policy choices or other differences between countries, until eventually it stabilized at an acceptable level.

Proposed in 1955, this was really a theory of the magical postwar years referred to in France as the “Trente Glorieuses,” the thirty glorious years from 1945 to 1975. For Kuznets, it was enough to be patient, and before long growth would benefit everyone. The philosophy of the moment was summed up in a single sentence:

“Growth is a rising tide that lifts all boats.”

A similar optimism can also be seen in Robert Solow’s 1956 analysis of the conditions necessary for an economy to achieve a “balanced growth path,” that is, a growth trajectory along which all variables—output, incomes, profits, wages, capital, asset prices, and so on—would progress at the same pace, so that every social group would benefit from growth to the same degree, with no major deviations from the norm. Kuznets’s position was thus diametrically opposed to the Ricardian and Marxist idea of an inegalitarian spiral and antithetical to the apocalyptic predictions of the nineteenth century.

In any event, the data that Kuznets collected allowed him to calculate the evolution of the share of each decile, as well as of the upper centiles, of the income hierarchy in total US national income. What did he find? He noted a sharp reduction in income inequality in the United States between 1913 and 1948. More specifically, at the beginning of this period, the upper decile of the income distribution (that is, the top 10 percent of US earners) claimed 45–50 percent of annual national income. By the late 1940s, the share of the top decile had decreased to roughly 30–35 percent of national income. This decrease of nearly 10 percentage points was considerable: for example, it was equal to half the income of the poorest 50 percent of Americans. The reduction of inequality was clear and incontrovertible. This was news of considerable importance, and it had an enormous impact on economic debate in the postwar era in both universities and international organizations.

Malthus, Ricardo, Marx, and many others had been talking about inequalities for decades without citing any sources whatsoever or any methods for comparing one era with another or deciding between competing hypotheses. Now, for the first time, objective data were available. Although the information was not perfect, it had the merit of existing. What is more, the work of compilation was extremely well documented: the weighty volume that Kuznets published in 1953 revealed his sources and methods in the most minute detail, so that every calculation could be reproduced. And besides that, Kuznets was the bearer of good news: inequality was shrinking.

The Kuznets Curve: Good News in the Midst of the Cold War

In fact, Kuznets himself was well aware that the compression of high US incomes between 1913 and 1948 was largely accidental. It stemmed in large part from multiple shocks triggered by the Great Depression and World War II and had little to do with any natural or automatic process. In his 1953 work, he analyzed his series in detail and warned readers not to make hasty generalizations. But in December 1954, at the Detroit meeting of the American Economic Association, of which he was president, he offered a far more optimistic interpretation of his results than he had given in 1953. It was this lecture, published in 1955 under the title “Economic Growth and Income Inequality,” that gave rise to the theory of the “Kuznets curve.”

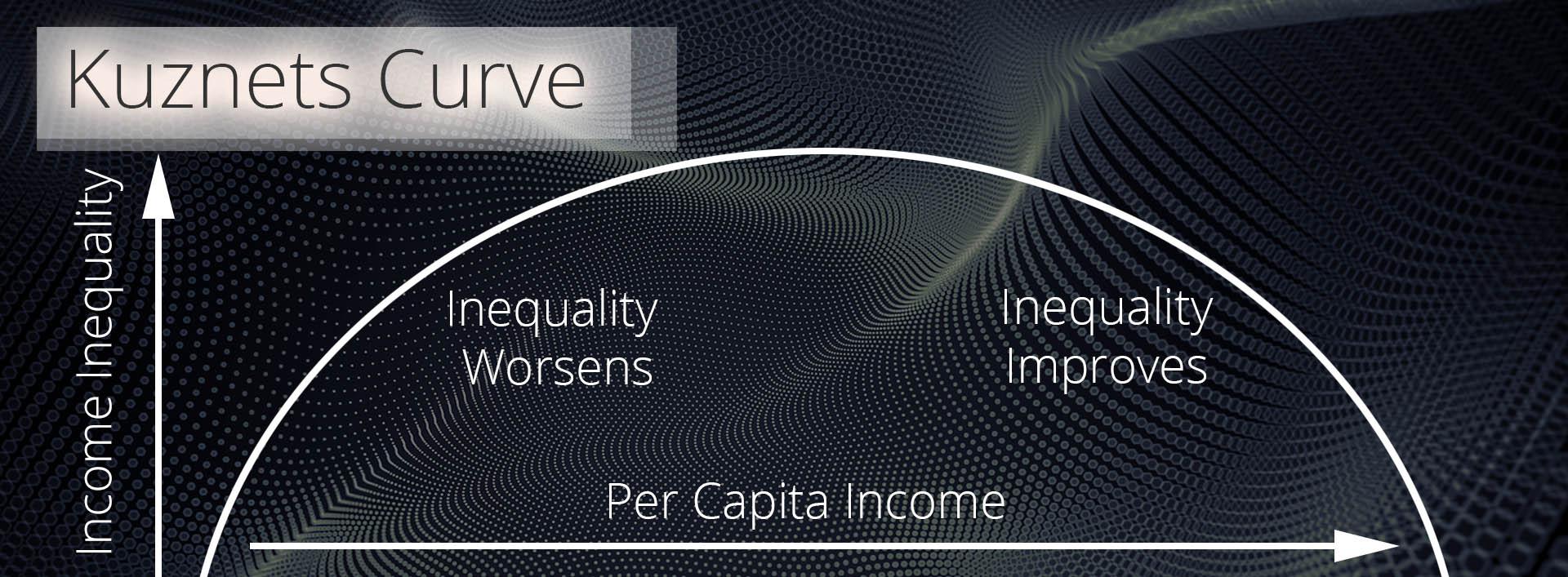

Above, we see the Kuznets Curve below, his optimistic idea simply that as industrialization increased at first, we would see inequality worsen. But as time goes on, inequality improves. This optimistic view was almost the exact opposite of Karl Marx, whose hypothesis was the opposite suggesting that inequality would simply get worse and worse as time passes.

According to this theory, inequality everywhere can be expected to follow a “bell curve.” In other words, it should first increase and then decrease over the course of industrialization and economic development. According to Kuznets, a first phase of naturally increasing inequality associated with the early stages of industrialization, which in the United States meant, broadly speaking, the nineteenth century, would be followed by a phase of sharply decreasing inequality, which in the United States allegedly began in the first half of the twentieth century.

Kuznets’s 1955 paper is enlightening. After reminding readers of all the reasons for interpreting the data cautiously and noting the obvious importance of exogenous shocks in the recent reduction of inequality in the United States, Kuznets suggests, almost innocently in passing, that the internal logic of economic development might also yield the same result, quite apart from any policy intervention or external shock. The idea was that inequalities increase in the early phases of industrialization, because only a minority is prepared to benefit from the new wealth that industrialization brings. Later, in more advanced phases of development, inequality automatically decreases as a larger and larger fraction of the population partakes of the fruits of economic growth.

Kuznets, like Ricardo and Marx before him, has created a future prediction based on what was happening at the time. Born in 1901, Kuznets’ view of the world was just like his bell curve. To illustrate, we shall look at the first graph from Piketty’s ‘Capital at the Dawn of the 21st Century’ (his preferred title).

Here, we see that in 1929, equality is peaking, and over the next 50 years it could fall within his curve. And that he was correct in recording the data up to realising his paper “Economic Growth and Income Inequality” in 1955. However, he failed to predict that the rebound from the wars and turmoil of the first half of the century, and from the 1990’s the rise of the ‘super manager’ would send income inequality in the opposite direction.

And while we are here, let’s look at the leading industrial nations of Europe, which follows a similar path to the USD, albeit the main shock was World War 1, and that the recovery of inequality was in 1950.

In all cases in US, UK, France, and Germany; the Kuznets Curve applies at the time Kuznets wrote about it.

The greater point that we see from these economists is that they looked only at what was happening to them at that time, and projected that idea forwards indefinitely, which in each case turned out to be wrong.

The moral of this story is that extreme hellish or heavenly predictions from the leading economists of their day have always been wrong going forwards. There is (I’d say) a portion of truth to all, but to make a prediction for 20 or 50 years’ time solely based on what one knows today continued forwards is likely to be wrong due to ‘Black Swan,’ the idea that something new will be entered in to the equation that will change it radically.

There are a lot of economists and politicians with a negative outlook for the USA and Europe, one of which we shall look to in just one moment. However, as a system that instead of predicting futures creates futures, that has inbuilt equality, for all the doom and gloom S-World will do great good and is the best ‘Black Swan’ (new important event) on the table. Albeit the creation of limitless free energy via fusion would equally be a massive change to the global picture.

Piketty asks:

“Will the world in 2050 or 2100 be owned by traders, top managers and the super-rich? Or will it be owned by the oil rich countries, or the bank of China? Or perhaps it will be owned by the tax heavens in which many of these actors will have sort refuge.

It would be absurd not to raise the question of who will own what, and simply to assume from the outset that growth is naturally balanced in the long run.”

I like Thomas Piketty, as he draws from many different sources, in fact in his book, it takes 10 minutes just to list them. Piketty presents an even-handed view of economics as a spectrum of probabilities, not predictions.

We can see S-World as a modern-day version of the optimistic Kuznets Curve, and we can see the antieconomic views of Keene, Schiff, and others as the worst-case scenario.

S-World Economics

S-World is not built upon the traditional micro or macroeconomic models, which is a good start for any new system. It has mostly been developed via business experiments and simulations and Theory of Everything (M-theory) physics simulations. However, recently, looking at economics has been helping to improve the system.

Peter Schiff’s ‘The Real Crash: America’s Coming Bankruptcy’ was a good find, as it made the economic case for American Butterfly’s ‘Theory of Every Business’ (circa 2012) US economic forecasts (more at http://americanbutterfly.org).

More recently, Tim Delmastro’s documentary that featured Schiff: ‘End of the Road: How Money Became Worthless’ helped to explain the dangers of ‘FIAT currency.’

In ‘The Real Crash: America’s Coming Bankruptcy – How to Save Yourself and Your Country’ by Peter Schiff, and Tim Delmastro’s documentary ‘End of the Road: How Money Became Worthless’; Delmastro, Schiff, and the other respected economists and financial experts named below tell of the end of gold backed US currency on August 15th, 1971. And how ever since the USD and the world entered into a ‘FIAT’ based currency system (where money could be printed at will) effectively creating a ‘so-called’ global dollar based Ponzi Scheme, that when it ends could (and in fact always has in history) create hyperinflation as was last seen in Zimbabwe in 2008.

The Cast of ‘End of the Road: How Money Became Worthless’

- Adam Fergusson

- Mike Maloney

- Bill Murphy

- Jim Puplava

- James Rickards

- Dimitri Speck

- Eric Sprott

- James Turk